Electric Slide: EVs in Motorsport

There’s a mantra inside motorsport culture:

Race.

Break.

Fix.

Repeat.

In a way, it’s this mantra that led me to purchase my first electric vehicle, a used 2016 Volkswagen e-Golf, a car which I often refer to as “the best car I’ve ever owned.” It’s everything that’s great about the seventh-generation Golf, plus the benefits of electric propulsion: The instant torque, the silky smooth and quiet powertrain, zero emissions. You know the deal. It’s everything I was looking for in an enjoyable daily driver.

A few years earlier, I had discovered what would become my favorite pastime, a grassroots motorsport called “autocross,” also known as “auto-x” or “Solo.” In autocross, drivers navigate a temporary, timed course defined by cones and chalk, featuring tight turns, long sweepers, tricky transitions, and a seemingly endless series of slaloms, as fast as their tires and driving skills permit. “It’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on!” local autocross veteran Joe Vance explained at my first event.

This was about the time when EVs – the Tesla Model 3, in particular – were earning a great deal of attention in the sport. Rightfully so.

The SCCA Solo Nationals, akin to the Superbowl of autocross, is a gathering of more than a thousand drivers from across the country to determine the best of the best in each class, groupings of similar performing vehicles. In 2019, David Marcus and his Model 3 sedan made headlines when he became the first EV competitor to win a national title, beating performance-focused sportscars in his class like the Shelby Mustang GT350, Lotus Evora, and fifty Porsches, BMW M-cars, Camaros, and the like.

The following year, the finale of the Optima Ultimate Street Car Series featured a World Championship Autocross event with a unique format: No classes. Winner-takes-all. Amid the most extreme autocross racecars sporting stripped-out interiors, high-strung race engines, and giant rear wings, driver John Laughlin piloted his mostly stock Tesla Model 3 to an impressive top-4 finish.

This seemed to mark an inflection point. At the pinnacle of motorsport, competitors are constantly seeking – and the sanctioning bodies seeking to eliminate – the “unfair advantage.”

To be clear, both Marcus and Laughlin are champion drivers, electric or otherwise. In a sport that comes down to maximizing, without exceeding, the available grip of your tires, driving in autocross is fundamentally about weight management, and 4000 pounds in motion is a lot of mass to keep control of at the limit! On paper, EVs would appear to be at a disadvantage.

That such heavy vehicles can dance alongside lighter, purpose-built sports cars is a testament to EVs at the pinnacle of current automotive technology: Tire compounds, a vastness of sensors, intelligent all-wheel-drive, and stability control systems. Yes, these technologies are available to other modern vehicles. But oh, that on-demand torque and the fact that all this integrated technology can be updated and improved by, say, 5% through over the air (OTA) software updates is… advantageous.

In SCCA Solo, the Tesla Model 3 Performance wasn’t just bumped into a higher tier class, it was thrown into the deep end of the autocross pool: The top-tier Super Street class, among supercars like the Acura NSX, Porsche GT3 and GT4, and the latest, greatest Corvettes.

And much like partygoers pouring onto the dancefloor when the DJ starts “Electric Slide,” more and more competitors are showing up to events in electric platforms. To accommodate, in 2021 SCCA also launched a provisional class dedicated to EVs called “EVX” (Electric Vehicles Experimental.)

We’ve seen other motorsports experiment with going all-electric in recent years. I’m partial to Formula E, with single-seater formula cars and tracks that feature “power boost zones” that must have been ripped directly out of Mario Kart. Fans of two wheels have MotoE and off-road enthusiasts have Extreme E. There have been several rallycross series, including RX2e, World RX, Project E, and SuperCharge. These are just a handful of examples.

There was even an all-e-Golf event as the FIA began testing its e-Touring Car format in 2016. It’s not surprising, given the e-Golf is essentially the same Mk7 Golf chassis shared with its ICE-powered cousins, the GTI and Golf R, commonly seen at any autocross event. And although the e-Golf is the heaviest of the family, with nowhere near the power or tech of a Tesla, it’s also 500 pounds lighter than the Model 3.

Now, if you’re thinking that this is the part of the article where I tell you about my exploits while autocrossing my e-Golf, I’m sorry to say that’s not the case. While I’ve certainly stepped one foot forward into electrification, my other foot -my lead foot, if you will- is still firmly stuck in internal combustion for autocross. And the reason why is embedded in the refrain of the mantra.

You see, when I first began autocrossing, I was looking for a way to enjoy the performance of my previous daily driver, a V-8-powered sports sedan. In a sport whose charm is partly based on the invitation to come out and drive, no matter your vehicle, in a safe, controlled environment, it was easy for me to believe that I could autocross on Sunday and drive to work on Monday.

This was before I understood the mantra.

Race.

Break.

Fix.

Repeat.

After having “broken” and then “fixed” the engine… twice, I made two important decisions.

First, to mitigate the personal anguish of future breaks, my daily driver was officially retired from autocross duties -and later replaced by the e-Golf. While serving as my faithful daily, the e-Golf won’t be subjected to my autocross antics. And since giving up my favorite clothed pastime is out of the question, like any sensible human being, I decided to pick up an inexpensive track car for autocross.

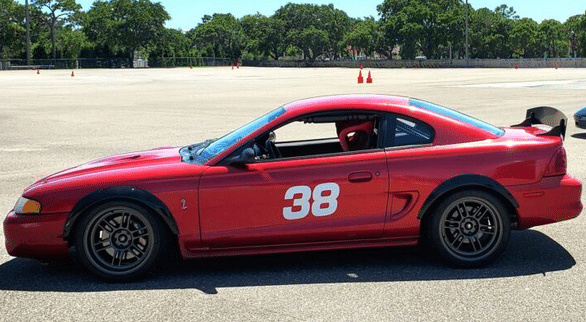

“Inexpensive” is the keyword, and this brings me to my second important decision. To mitigate the cost of future fixes, as much as possible I perform them myself. Note, I’m not an engineer by trade –at most, by relation– but over the years, I’ve learned to turn a wrench, especially on V-8s. It’s one of the many reasons why I chose a 25-plus-year-old Mustang for my track car. With 1.5 million Mustangs sold between 1994 and 2004, there’s plenty of aftermarket support and donor cars for parts.

The same can’t be said for the e-Golf – at least, not yet. On the rare occasions I pop the hood, it’s all metal boxes and wires that warn of sudden, painful death if I touch them. I, and the aftermarket, have a lot to learn about these new electric powertrains.

Still, every time I pop the hood of the Mustang, I wonder how much longer I have until some engine component finally breaks for good and leads to catastrophic failure. If that happens sometime in the near future, I might have some additional aftermarket options to drop in.

Late last year, Ford surprised enthusiasts by offering the electric powerplant from the Mustang Mach-E GT Performance Edition as a crate motor, called the “Eluminator” (a clever play on the V-8 “Aluminator” crate engine name.) While Ford sold out of the Eluminator in days, it’s clear that demand for electrification among automotive and motorsport enthusiasts is surpassing expectations.

Whether retrofitting an electric powertrain into my current track car or replacing it with the e-Golf after purchasing my next EV daily driver (I’m on the reservation list for both the Ford F-150 Lightning and Chevrolet Silverado EV), I’m looking forward to my own electric slide.

Written by: Ricky Frohnerath