The End of the ICE Age: Rise of the Chinese NEV

Bill Russo is the Shanghai-based founder and CEO of Automobility Limited, a strategy and investment advisory firm helping its clients to create the future of mobility. His over 35 years of experience include 15 years as an automotive executive in China and Asia and nearly 12 years in the electronics and information technology industries. Bill is also currently serving as the chair of the Automotive Committee at the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. In his current role, Bill advises startups, corporations and investors on how to maximize their participation in China’s Automobility Revolution. Bill was previously the regional head of Chrysler in North East Asia.

Below is a July 2023 interview with Russo, compliments of AMCHAM Shanghai.

You recently attended the Shanghai Automobile Show, which some observers described as a wake-up call for legacy automakers, including German and US manufacturers. What were your three biggest takeaways from the auto show?

When you look at what’s happened in China over the course of the pandemic and even in the years prior, this market has dramatically changed. The rest of the world [used to] perceive China as a place where foreign companies came, brought their know-how and technology and Chinese companies were following. It’s not that way anymore. Chinese companies in the EV era are leading development and innovation. There is a race to the middle, which means you can no longer just sell a cheap, affordable product. You must sell a well-contented vehicle at an affordable price point. That’s a discrete lane dominated by BYD, now the number-one selling brand in China, even larger than Volkswagen, which has perennially held that position.

There’s also a lane in the market for what I call the smart EV — companies born in the era of the digital economy. That’s what’s special about China; it is the world’s largest digital economy. It has companies that were created by investment from the internet economy, like NIO, Xiaopeng and Li Auto. Publicly listed companies led by entrepreneurs are far more digital at the core. They understand that a Chinese consumer looking at a technology purchase, which an EV is, wants more than just an electric power train. They want a digitally connected experience. Chinese electric vehicles pay far more attention to the human machine interface — the ability to speak to and interact with a lot of digital app-based solutions in-vehicle.

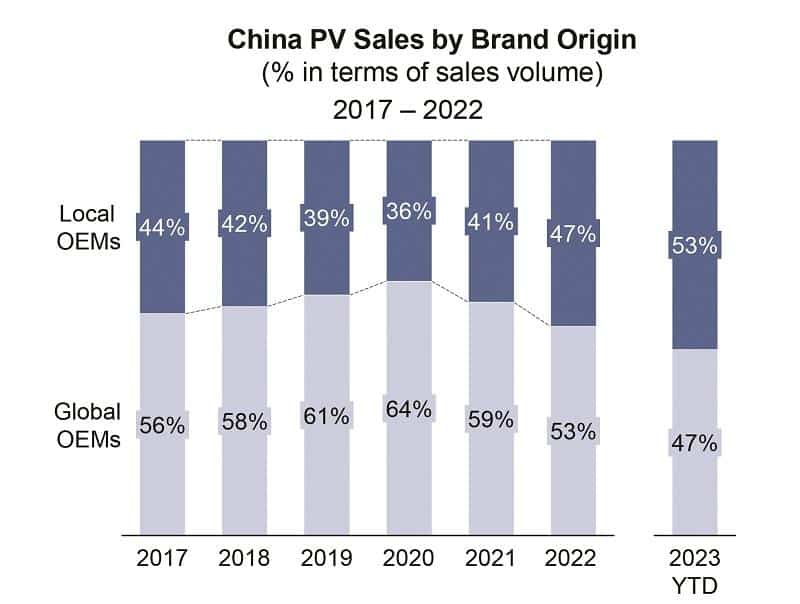

Foreign companies have, in the span of the pandemic, lost the edge. They’ve gone from being more than 60% of the market in 2020 to now less than half. This is the first time in the post-Mao era that Chinese brands have outsold foreign brands in China. That’s shocking for a lot of the foreign executives that visited here.

And do you think they’re worried now?

Alarm bells are going off. China as a market is too big to fail in, especially if you’re a European company. European luxury premium manufacturers such as Mercedes, BMW and Volkswagen’s Audi have derived the largest profits and sales revenues from this market. If you lose China, you lose your competitive edge, and not just in China; you can derive from China the economy of scale that allows you to be more competitive in your global business.

Losing China is a huge blow to all of the global automakers, but to the Europeans in particular. The Japanese are more focused on the US market. The American companies are less dependent on China, although they’ve had eras of success here. Tesla still has 10% share of the EV market in China. Ford and General Motors are experiencing some pain now, but they have a home market of significant size and scale to fall back on.

Is it too late for foreign automakers that were focused on internal combustion engines (ICE) to make the leap to electric in China?

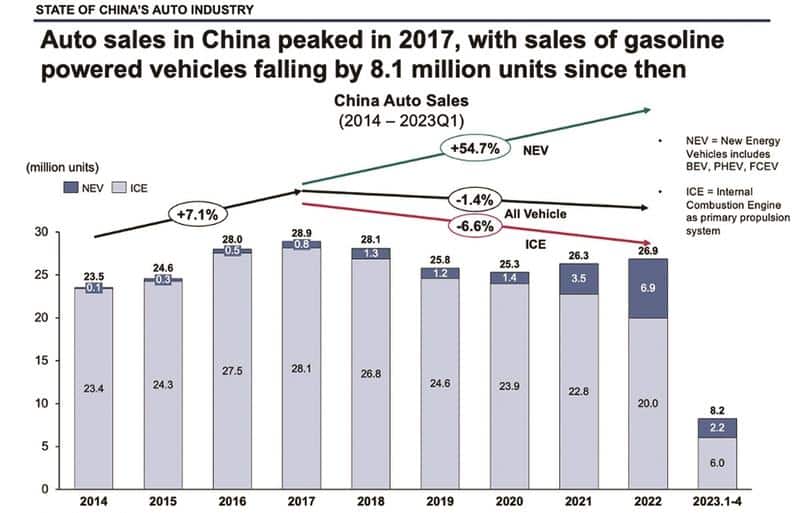

It’s not impossible but it’s much more difficult. In 2017, the peak year in China’s auto industry, 28.9 million vehicles were sold, of which 900,000 were electrified. That’s a 3% share. Fast forward to 2023 — about the length of a product cycle in the automotive industry. Last year, 26.9 million units were sold. The market shrank by two million units in that six-year period. Of those 26.9 million units, 6.9 million vehicles were new energy vehicles. That means a decrease of eight million ICEs. The writing is on the wall.

If in 2017, you were planning vehicles heavily weighted toward ICEs, you’ve watched your market share get completely eroded. The automotive industry planned for an incremental growth of electrified vehicles in China. What they got is exponential growth. That’s how it happens in China. With companies backed by internet investment capital, and some like BYD with vertically integrated supply chains that can scale far more aggressively than the foreign companies, overseas companies have no other choice. If you want to stay relevant in China, you must find a way to get back in the new game.

How beholden are American manufacturers in China to Detroit’s directives? Do they have liberty here to push electric?

Tesla does not have any loyalty back to Detroit. They’re not beating by the same drum. Let’s talk about the success of Tesla’s entry into China. Since 2018, when China changed its to allow foreign brands to own the majority, if not the entirety, of their operations in China, Tesla was the only company to do so in the passenger car business. Why? Foreign companies are addicted to milking the old cow. It reflects the lack of commitment or conviction to the EV market in 2018. And any moves with the intention of pivoting would be an affront to the local partner that they already had a joint venture with, in which they’re profiting from traditional vehicles. I call this carry-over bias.

The internal combustion engine was invented in the late 19th century by Karl Benz and has had 138 years as the dominant intellectual property of the automotive industry. The lack of conviction to electric vehicles is the albatross that’s holding the traditional automakers back. Their carry-over bias also includes a risk-averse system that doesn’t prioritize bets outside of the ones that you can put a high degree of confidence in winning. Until now, the proposals about EVs that have gone to boards have a lower net present value [than ICE], because they have higher costs and lower volume with lower unit margins. If the finance team tries to mitigate this by carrying over the instrument panel, chassis architecture or whatever else was in the legacy car, then you will have an EV ladened with carry-over technology. That’s what we saw at the auto show: late attempts by auto companies to make EVs, but what they’re going to make is similar in appearance to what they made before in China. That just doesn’t work. The Chinese customer wants a vehicle that screams technology — bigger screens, internet connectivity, self-driving features, and chatbots. This is a software-defined experience, not just a hardware or driving-centric experience.

If you were invited to the boardrooms in Wolfsburg or in Detroit, what advice would you give?

Commit to an exponential strategy in China. You must decide whether you’re going to be in China, for China; or in China for the world. Tesla’s approach is that they committed to China for the world. They put [their factory] in an export zone. They didn’t plan to only sell cars. A significant quantity of the vehicles — almost half — are exported from China. Why are they doing that? Is it to take jobs away from overseas markets? No, it’s to make the products that they build everywhere in the world more cost-effective because they have the economy of scale of the world’s largest EV market inside of their system. You can take these benefits and apply them to the components that you’re assembling in the United States, Mexico, Europe or wherever else you have a factory.

In which area of the EV automobile are Chinese automakers besting their Western counterparts?

If you get in a Chinese EV, you don’t even have to drive it to know it’s different. Chinese EVs have a lot more screen space and technology features that would delight you as a 21st century consumer. That’s who [the brands] are targeting. One of the advantages that China has had historically is a younger buyer. When I worked for DaimlerChrysler, Mercedes buyers in China were about a generation younger than Mercedes buyers overseas. They were in their 30s, not in their 50s. Chinese wealth rose later; people in the second half of their lives didn’t have the same opportunities that the younger population have. The younger generation express that with what they buy, and buying a car is a prestige purchase. If you’re a Millennial, Gen X or Gen Z, you want your car to be a technology platform. You want to brag about the technology features. The acceleration, the driving characteristics, are not as important.

Is Chinese success in EVs a result of not being encumbered by ICE engines? Is it because of these companies’ innovative mindsets? Or is it a bit like the telephone, where in China everyone went from having no phone to having a mobile phone, so they had a built-in technological leap that the West hasn’t been able to experience?

There is a lack of multi-generational habits. Nobody has the same life as their parents and grandparents. Every generation is experiencing a different lifestyle and set of opportunities and choices. That means there’s less legacy and less handed-down behavior. Highways and transportation networks are relatively modern in China. Companies doing business in China recognize that things can change quickly. Foreign brands are living in a parallel universe where incrementalism prevails. In China, people have learned new behavior. There was a copycat mentality here 20 years ago, as well as in Japan, Korea and other countries that started later in their development. What’s happened in the last decade is Chinese companies have broken away and started to create a different objective with a more experimental mindset, and a whole lot more attention to digital and connectivity. Advanced technology gets commercialized more rapidly in its scale because of the size of the market.

There is a belief that manufacturers like BMW and Mercedes enjoy a sort of protective moat because of their reputation, brand power and engineering. Is that going to protect them from the likes of BYD?

It gives them a little bit but not an infinite amount of time. You can’t build your castle on sand that’s eroding out from under you. What they do have is a foundation built on heritage as a prestige brand; they have mechanically engineered technology, driving-centered performance, certain features like the sound of the door when it slams. I saw a post about Germans at the BYD stand, slamming the doors on the BYD Seagull, saying they still don’t know how to make the door slam the way ours can. But people are not buying that car because the door slams a particular way; they’re buying because it’s $11,500, and the car you’re selling is far more expensive.

In China, you now have a clock ticking, telling you to get on board with whatever has just changed. Around 2012-2013, SUVs became popular and Chinese consumers were flocking to them. Chinese companies, led by Great Wall, started building many different types and varieties of SUVs and grew their market share from less than 40% to about 45%. In 2017, foreign brands introduced SUVs such as the Volkswagen Tiguan, among other products. Between 2017 and 2020, foreign brands’ market share went back up to above 60%. Chinese consumers do still have an esteem for the legacy brands. But that was an incremental move; [these foreign brands] knew how to build SUVs, they just weren’t building them in China. Can they do that for EVs? This is different. Chinese EVs are fundamentally offering a different value proposition than just an electric powertrain. People are expecting a smartphone on wheels, not just an electric powered vehicle.

What’s made BYD so successful?

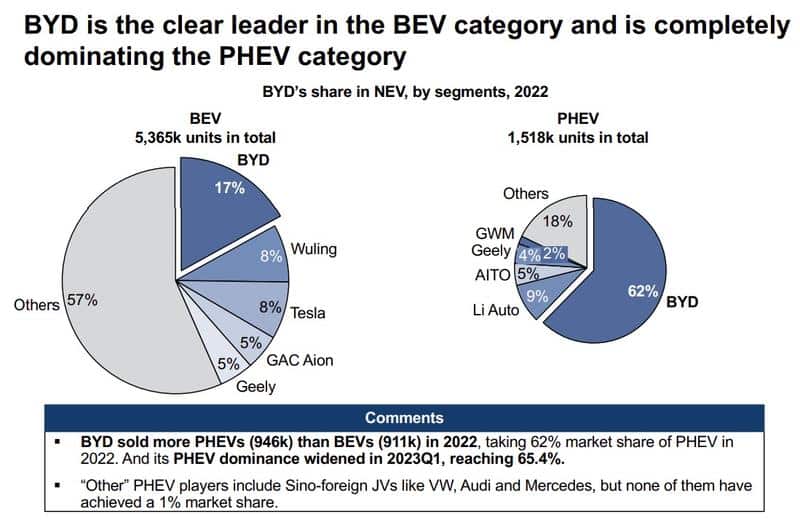

First and foremost, they are entrepreneur-led, not a state-owned enterprise. That’s fundamental because the world tends to paint China with one stroke, saying a company is succeeding because they’re controlled by the government. BYD is a publicly traded private business. Warren Buffett was their pioneering investor when BYD was a battery company becoming a car company. Now, 15 years after that investment, they have 40% share of the EV market in China. They started out making combustion engine-powered vehicles, then making plugin hybrids, and now making BEVs and selling them at volumes unseen anywhere else before. Why are they successful at doing that and others are not? They make batteries; they were a battery company before they were a car company. They have a vertically integrated supply chain and control of the highest cost component in a vehicle. They even have control of some of the other components that go into the electrified vehicle, including chips that are purpose-built for their vehicles.

Does that upend the way that other manufacturers think?

It turns the whole price-value equation upside down. Whereas Tesla aspires to build a $25,000 EV someday and Volkswagen aspires to build a €25,000 EV someday, BYD can build an $11,500 EV right now, because they have that vertically integrated supply chain working for them.

In terms of EV technology, when the industry matures, what will be dominant? Plug-ins or pure EVs? What is the future for hydrogen-powered cars?

China uses the term “new energy vehicles,” which is inclusive of battery electric, plug-in hybrid and fuel cell electric vehicles. That basically places bets on all three. What China has done, which the rest of the world has not, is pay more attention to infrastructure. The automotive industry didn’t scale without an investment in infrastructure, mainly highways, roads and gasoline stations. That investment was not all on the back of the automotive industry. There was a lot of investment from government. China is very good at, and the rest of the world is slow at implementing, public-private partnerships to create the conditions for new innovations to come to market.

If you had $1 million and were asked to bet on one of these technologies eventually trumping all the others, where would you place your bet?

It all requires infrastructure. If it’s a fuel cell, it requires hydrogen storage and distribution, which needs to come from government investment to get started. BEV was more expensive until China came along and scaled things with a battery chemistry — lithium iron phosphate — far lower in cost and therefore price for the consumer. China made choices that made the democratization of the BEV possible, and that was led by BYD and CATL.

The plug-in hybrid is an interesting case because it’s a lane with fewer competitors. Right now, BYD dominates the plug-in hybrid category. More than half of their vehicles are plug-in hybrid-equipped, and they have two-thirds of the market. They have 17% of the BEV market and 67% of the PHEV market. That has to do with legacy; BYD didn’t start as a BEV-only company. They had gasoline-powered vehicles, so they adapted gasoline engines as backup generators for creating the electricity stored in the battery. They did something that the rest of the world has not prioritized, and that gave BYD a dominant position in a lane that is smaller in size but growing.

The long-term bet for the passenger vehicle is BEV. For the commercial vehicle, if it’s 10 years, it’s probably a fast charging or battery-swapping BEV; if it’s 20 years, then it could be fuel cell. It depends on how committed China is to continue investing in a business that doesn’t have a near-term commercialization opportunity, because nothing happens without losing money at first. They did it for BEV by putting the world’s highest density of electric vehicle charging facilities. They’re investing in battery swapping for certain use cases for ride-hailing type vehicles, for fleet-oriented vehicles that move around frequently. They’re also investing in fuel cell experimental zones for commercializing that technology. China will have the advantage in the public-private partnership aspect of how they do business.

You’ve said that the number of Chinese EV manufacturers must shrink. How many will exist in 10 years’ time and which ones will become international players?

It won’t take 10 years to consolidate. The top five NEV companies in China command two-thirds of the market and the top 10 command 80%. If there’s more than 100 players, then that means 90 of them are sharing 20%. Those companies will either consolidate or go away in a time frame of probably five years.

How many will there be? The China government won’t give up on the central government SOEs. They are legacy businesses, less market-oriented and are too big to fail. This includes FAW, Dongfeng and Chang’an. Some regional SOEs like Shanghai Auto (SAIC) and Guangzhou Auto (GAC) have a stronger market orientation and can make it on their own. For the private-owned companies, there will be BYD, Geely and Great Wall that are nimble and have a proven ability to succeed in the market. Cities and provinces in China are as large as European nations in population size, so there’s enough business in their home province to be successful for a bit of time even for regional players. While their business models are more experimental, a few of the Smart EV players like LI Auto and NIO are also starting to gain traction.

In terms of succeeding globally, in the SOE class, Shanghai Auto has the most experience. They’re already established with the MG brand overseas. Of the private-owned companies, Geely is already global since they own Volvo, Lotus, Polestar and Lynk & Co. These brands already sell well internationally. And BYD for sure. Interestingly, BYD sold fewer than 60,000 units overseas last year [out of over 3 million exports from China], which is an anomaly for a company that’s so dominant at home. That’s because every car they make, they can sell here. They don’t have an overhang in capacity and are chasing demand, but the world has woken up to BYD’s value proposition and there’s high demand for BYD to go overseas now. You’ll see that happen very quickly.

* includes VW-SAIC and VW-FAW, and the sales data is estimated)

If European and US automakers fall behind their Chinese counterparts, do you anticipate the EU and US imposing tariffs to protect their domestic auto manufacturers from Chinese competition?

There’s no question as to whether they’ll do it, but I question the logic. They’ll do it because they think China created an unfair game that favored the home team. There is some truth that China’s policies intend to create a domestic competitive advantage; that’s what governments do. That’s what Japan did for its semiconductor industry and auto industry. Auto industries are too big to fail for the home team, so national governments tend to create policies [to support] the home team. That was true for EV development, particularly with battery technology. China didn’t allow foreign companies to use foreign-sourced batteries; they had to build factories here. They’ve since relaxed some of the regulations, but it gave China a head-start on the electrification race.

The knee-jerk response from national governments will be to erect barriers to entry for Chinese technology. That will do two things. First, it will make your domestic competitors less competitive. If you’re not racing at the Olympic level, then you will be weaker in your ability to compete globally. You want to be in China because you need to compete at that level. I give credit to Tesla because they’re here for the purpose of making themselves better as an EV company; they’re racing with the fastest companies in the world. Protecting your domestic companies from competing at home will only make them more dependent on [the] government. Let the fastest horse races and beat them. This doesn’t mean run faster than them today. It means developing the tools and the technologies that make you better than them. For American innovation in electrification, we owe a lot of credit to Elon Musk and Tesla for being the pioneer. That was not going to come from the likes of Ford, General Motors and Stellantis.

How siloed do you expect the US and Chinese auto industries to become? Will data security laws in both countries mean that both countries end up running entirely different navigation and vehicle management software? And do you see room for Chinese and American auto industry suppliers to keep selling into both markets? Or will there be barriers because of data security?

Data security is the most problematic [issue] because it requires having two solutions for the China and non-China regions. The risk, if you don’t have a standard way of doing things, is it creates dis-economies of scale since you must create separate solutions for different markets. It’s a little less problematic in software and data. Although there’s technology that would need to be re-architected, the bigger problem is if the hardware may need to be different in the two places, because that’s a lot of capital expenditure and manufacturing investment.

A lot of the push-back to having different standards in place is because companies don’t want to bifurcate; they would rather be global in their capital expenditures. But it makes sense to have regionally deployed R&D with some level of adaptation to what your base solution is. The digital solution sets in the West and in China will be different. The question really is, what will happen if China does go global toward markets where international companies must then choose? If Chinese competition comes to Europe and brings a solution that becomes a standard by which others will be judged, does that mean the European countries have to adapt more to the way the Chinese have designed their smart vehicle? What does that mean to the supply chain for the technologies that go along with that?

The question will come in the advanced driver assistance system (ADAS), the early form of autonomous technology. As ADAS scales, it will be the most problematic area for European and American global companies to participate in China. You will have to make modifications. Will those modifications find their way back to the home market? Chinese companies will bring their solutions internationally and there’s no way a way to prevent some form of clash between the two worlds in the future of autonomous mobility.

Some Western suppliers have been very successful selling to both foreign and Chinese automakers. What future do you see for those Western suppliers in China?

They have the same dilemma of being carry-over biased. As legacy businesses, they profit from the architecture of the traditional car. Seeing [the supply chain] migrate to something else more electronic and less mechanical is a disadvantage to those companies. The more progressive brands are investing in new technology; how aggressively they deploy in the China market remains to be seen, but the Chinese recognize that tier ones in the global supply chain, on which they have been dependent, may not move at the same pace as China, so they will create their own tier ones.

You’re seeing it with the likes of Huawei stepping in as a automotive technology supplier; ECARX, a joint venture between Geely and Baidu to build smart cabin technologies; and Alibaba and SAIC creating Banma for in-vehicle, intelligent connectivity technology. CATL, an EV battery-maker, is building infrastructure for battery swapping; they see themselves as a platform for integrated chassis architecture that revolves around the electric power train. A new class of Chinese tier ones will come into being in the electrified area. That will set a new pace for competition in the global supply chain.

That brings us back to the BYD advantage, right? Not having to rely upon the suppliers because they have their own.

Yes, you could argue that BYD’s battery roots position them to be a supplier of EV technology to the rest of the industry. BYD sells battery technology to other companies, including Tesla. The strange evolution of this industry is that it will not be purely about who competes with whom, but also about who collaborates with whom, because that’s a way to mitigate some of the consolidation risk. If you’re a sub-scale player, stand on the shoulders of those who have scale for the critical technologies you will need in your vehicles. You don’t have to build a quantity of several million. You could be profitable with a lower quantity if you have the economy of scale of the companies with larger supply chains working for you.

What parallels are there between the rise of Japanese automakers that we saw in the 1970s and their entry into markets like Europe and the US, and the arrival of Chinese EV makers?

It is similar but not the same. Japan was an incremental threat. They turned the mass production model into a lean production model and created a quality-oriented business model. The Koreans came later with their own value proposition based on affordability. Both Japan and Korea have proven that Americans are okay if a product comes from an East Asian country – if it delivers good value for money. Americans already buy a whole lot of products from China, just not cars today, though a lot of the cars that are made in the US have Chinese components. The final act will be when the China cars come to the US and eventually get made in the US, which is somewhat inevitable unless you put up a trade barrier to prevent it from happening. But the difference is that, not only are the supply chains more scaled and China able to build at low cost, but China is also delivering an affordable technology value proposition. There’s a lot more content in these Chinese vehicles, available at a much lower price point. China is not just selling a cheaper car that happens to be an EV; they’re selling a technology product. That’s what the executives who came to the auto show saw. When the iPhone came, Nokia was on its deathbed. The ICE is on its deathbed now. The world is going electric vehicle, but it will also be going to digitally connected, software-defined vehicles. That’s what they’re making here in China. Japan didn’t do that; they only created an incremental improvement to a car like what the Americans were producing. China is creating an exponential improvement to the fundamental architecture of the next generation of vehicle.

Republished with permission from AMCHAM Shanghai.